Recently I procured a copy of the blacklisted Walt Disney classic Song of the South (1946) through eBay, and the movie was everything I remembered and nothing like I was led to expect.

What I remembered was being a thoroughly charmed and entertained six-year-old. That happened again at age 57 last week. Due to the absurd uproar over the movie, what I expected was nowhere to be found. Does Song of the South have some racial issues? Sure, but nothing that justifies Disney’s Orwellian erasure.

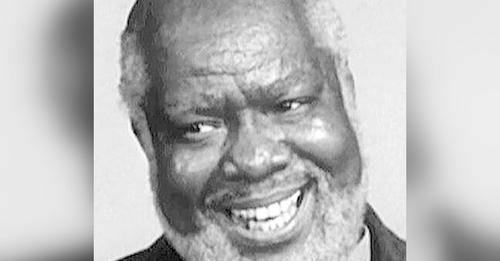

Song of the South, poster, top: James Baskett, from top left: Br’er Rabbit, Br’er Fox, Br’er Bear, Br’er Fox, Br’er Rabbit, Br’er Fox, Br’er Bear on 1956. (LMPC via Getty Images)

Overall, Song of the South (like its source material) is about healing the rift between black and white America and does so in racially progressive ways unheard of in 1946.

Despite this fact, due to thin-skinned and wildly misinformed criticism, Disney has blacklisted Song of the South since 1986—the last time it enjoyed a theatrical release. What’s more, the movie’s never been released on home video in America. Not even on laserdisc or Betamax.

Trust me; there’s no moral justification for this.

Song of the South is about seven-year-old Johnny (played by the sadly doomed Bobby Driscoll), who’s told he’s about to enjoy a vacation on his grandmother’s Georgia plantation. The truth, though, is that his parents are having problems. Dad is going away. This explodes Johnny’s security and leaves him without a father figure.

Before arriving, Uncle Remus (James Baskett) and his storytelling abilities are already legendary to Johnny, and his meeting with the legend does not disappoint.

To help Johnny work through his various problems, Uncle Remus uses parables—black folktales starring Br’er Rabbit (voiced by Johnny Lee in two sequences and Baskett in one). These delightfully funny animated sequences co-star Br’er Rabbit’s nemesis Br’er Fox (Baskett again) and Fox’s sidekick Br’er Bear (voiced by Nick Stewart).

There are a total of three cartoon parables. The first reminds Johnny (and us) that you can’t run away from your troubles. The second (the tarbaby) teaches Johnny not to manufacture problems for himself. The third teaches Johnny to use his brain instead of his fists (especially when outnumbered).

Not only is Song of the South a wonderful movie full of important life lessons—especially about forgiveness and honesty- but plenty of movies with worse racial issues are available everywhere today. Off the top of my head… Willie Best’s Algernon character in High Sierra (1941), the “Abraham” sequence in Holiday Inn (1942), and the Mickey Rooney scenes in Breakfast at Tiffany’s (1961)… All you can do is shake your head and wait it out.

However, good-natured stereotypes (including from my own background) do not offend me because I’m a rational adult. My rules are simple: as long as the portrayal comes from a good place and is dignified, I don’t even have a problem with a person of one race portraying another. For example, this is an act of pure love from Fred Astaire, a major movie star and white man, paying tribute to and recognizing a black trailblazer.

This is not okay.

Not to belabor the point, but Paul Muni’s portrayal of a Chinese man in The Good Earth (1937) is superb, nothing close to offensive. Katharine Hepburn’s portrayal of a Chinese woman in The Dragon Seed (1944) defines left-wing condescension. Willie Best makes me wince in High Sierra but steals Ghost Breakers (1940) right out from under Bob Hope. The difference in Best’s characterizations are subtle, but they are all the difference.

Let’s look at the complaints about Song of the South, some of which are valid, none of which justify this shameful blacklisting…

The movie portrays a southern plantation full of happy slaves

Lie.

The movie makes it perfectly clear that the story is set post-Civil War. Within ten minutes we’re told Uncle Remus is free to leave the plantation whenever he wants. The black characters are not slaves. They are employees and sharecroppers. At the movie’s end, in broad daylight, Uncle Remus (this is not a spoiler) does leave the plantation.

The black characters are stereotypes

True.

The black characters are subservient to white characters and speak in an exaggerated “sho’nuff” dialect. However, this is also true of some of the white characters, specifically the two boys who bully Johnny. Both are something right out of Lil’ Abner or Ma and Pa Kettle—a popular film series from the same era that affectionately stereotyped white southerners in the same way Song of the South does black southerners.

Uncle Remus is an Uncle Tom

False, false, false…

Yes, Uncle Remus is subservient to the white characters, but he’s 1) a dignified gentleman to everyone, and 2) works for these white people. But he is certainly not some scheming, scraping Tom. Plus, was this subservience not a sad reality of the Reconstruction Era? It seems as though the same people who (falsely) accuse the movie the portraying a false reality of happy slaves also oppose the reality-reality of the unfortunate social structure that arrived after the Civil War in the Democrat-run South.

Nevertheless, within this reality, the movie grants Remus a straightforward mind and will of his own.

The movie’s use of the “tarbaby” is racially degrading.

Totally false.

I kept waiting for Br’er Fox to dress up that tarbaby like an exaggerated black man, something out of a minstrel show. There’s none of that. Tar is used for metaphorical not racial reasons. The tarbaby is given no racial characteristics. Using “tarbaby” as a metaphor might be “racially insensitive” today, but that has zero to do with Song of the South.

Uncle Remus is a “Magic Negro”

Somewhat true. The fact that Baskett is the movie’s star negates some of this. Uncle Remus is also not subordinate to the white boy he’s helping—he’s a father and authority figure. Finally, Uncle Remus is more than beatific. He experiences and expresses anger, disappointment, and rejection, not to mention the complicated emotions that come with being falsesly accused. He’s a full character, not just a symbol.

Equally important is what you don’t see. No one is called “boy.” No one is called “massa.” Even when the white people come into conflict with Uncle Remus (more on this below), these white people treat him with dignity and respect. In fact, none of the black characters are degraded or disrespected, nor do they behave in a demeaning way. On the contrary, the three main black characters—Uncle Remus, Aunt Tempe (the great Hattie McDaniel), and Toby (Glenn Leedy), all enjoy a familial affection with their white employers that never stoops to condescension or treats them like pets.

The above doesn’t matter as much as what Song of the South has to say, what its theme is. Anyone who judges a story’s morality on that story’s content is a moron. If content were the guide, the Bible—which is full of human depravities—would be one of the most immoral books ever written. Content is only the road upon which the moral (or theme) is driven. What matters is the destination, and this is where Song of the South takes us…

Uncle Remus is a black man in a 1946 movie who is the star of the movie. Additionally, his character is the moral center of the story; he is its moral authority and a father figure to a white boy.

How many movies aimed at the general public pre-Sidney Poitier can say that?

Here’s the other thing… In Song of the South, all white people are wrong, and Uncle Remus is right.

There are two heartbreaking scenes where, due to a misunderstanding, Johnny’s mother, Sally (Ruth Warwick), instructs Uncle Remus to stay away from her son. Now, as I mentioned above, both scenes are handled beautifully. Although she, of course, has the final say regarding her son, and Uncle Remus respects that, no one is spoken down to. That, however, is not the most important thing…

What matters is that Sally is a white woman falsely accusing a black man of something he’s innocent of. Even later, after she “catches” Uncle Remus not honoring her wishes, she never pulls racial rank on him. The audience knows she is wrong, and our sympathies are with Uncle Remus.

Also worthy of note is how Johnny’s black playmate, Toby, is treated as an equal. They’re pals, and Leedy steals every scene, which wasn’t easy with a young Bobby Driscoll next to you.

Equally important is the fact that Br’er Rabbit is an intelligent, funny, and very independent “black” character teaching a white kid life lessons. Of course, the thin-skinned (like the Apu idiots) complain that Br’er Rabbit, Br’er Fox, and Br’er Bear speak in exaggerated black dialects, and they do! But how is this different from any character of any color in any comedy cartoon? Elmer Fudd, Yosemite Sam, Bugs Bunny, Foghorn Leghorn… Seriously, y’all, grow up.

Plus, the three men who voice those “black” characters are black actors, not white. That should count for something in 1946.

This movie is about two things: 1) a black man helps a white kid come of age, and 2) racial reconciliation through mutual respect.

The true outrage about Song of the South is that the great James Baskett earned a well-deserved Honorary Oscar for his iconic work as Uncle Remus, and today, this iconic performance by the first black actor to earn an Academy Award has been disappeared by Disney’s Woke Nazis. What’s more, Baskett still holds the only Honorary Oscar in history ever awarded for a single performance. Sadder still, Song of the South was Baskett’s final performance. He died just a few months after receiving that Oscar.

And now, no one is allowed to experience James Baskett’s triumph.

Two other Song of the South Oscar-winners have been disappeared: Allie Wrubel and Ray Gilbert, the co-writers of the Best Song Oscar for the infectious “Zip-a-Dee-Doo-Dah.”

Sadly, things are getting worse. In the McCarthyite aftermath of the 2020 Antifa/Black Lives Matter Riots, “Zip-a-Dee-Doo-Dah,” James Baskett, and Br’er Rabbit have been completely erased from Disney theme parks.

We’re going backward, not forward.

Song of the South is delightful, heartwarming, and brimming with a humanity and empathy that lingers for days. Honestly, the worse anyone can accuse the movie of is being old-fashioned.

Nothing justifies blacklisting any kind of art, but erasing James Baskett’s well-deserved place in cinematic history—disappearing that man’s legendary and iconic accomplishment is infinitely more obscene and racially condescending than anything in Song of the South.